Context: why a digital microplan?

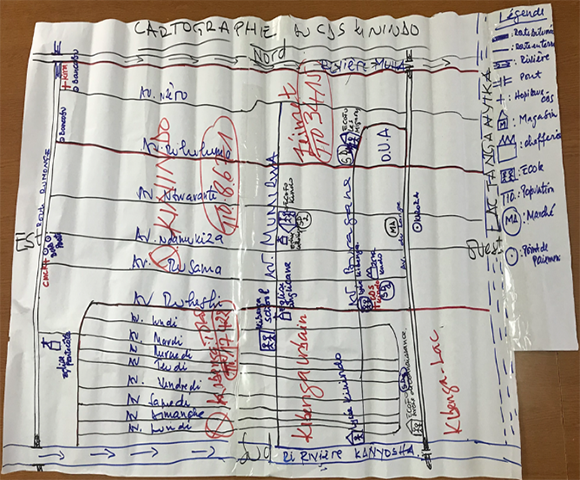

The Burundi National Integrated Malaria Programme (NMP) is planning an ITN mass distribution campaign for universal coverage in June 2022 with three ITN types (standard, PBO and dual active ingredient). The NMP organized and completed the microplanning exercise for all the 43 targeted districts in February 2022. Microplanning is a critical phase to ensure a successful distribution campaign as it brings local knowledge and context to global planning. The starting point of microplanning workshops is mapping, which is a crucial first step to producing quality microplans. As in previous campaigns, district teams used flipchart paper to hand draw maps of health facilities and their catchment areas, distribution points and additional features such as markets, schools and religious institutions, as well as population groups that have known barriers to access health services.

The Burundi National Integrated Malaria Programme (NMP) is planning an ITN mass distribution campaign for universal coverage in June 2022 with three ITN types (standard, PBO and dual active ingredient). The NMP organized and completed the microplanning exercise for all the 43 targeted districts in February 2022. Microplanning is a critical phase to ensure a successful distribution campaign as it brings local knowledge and context to global planning. The starting point of microplanning workshops is mapping, which is a crucial first step to producing quality microplans. As in previous campaigns, district teams used flipchart paper to hand draw maps of health facilities and their catchment areas, distribution points and additional features such as markets, schools and religious institutions, as well as population groups that have known barriers to access health services.

Immediately following the paper-based microplanning, Burundi’s NMP implemented a pilot project to digitalize the mapping process of a small portion of the country using geographic information systems (GIS) and satellite/aerial imagery to improve the quality and accuracy of the microplans. This pilot will generate important lessons in digitalization of the microplanning process, with the hope of extending digitalization to the whole microplanning process in future campaigns. The microplanning pilot for the ITN campaign is part of a larger digitalization effort funded by the Global Fund through its COVID-19 Response Mechanism (C19RM).

How was it done?

As a first step, the NMP identified the area targeted for the project, nominated staff for the pilot, recruited two GIS consultants (one national and one international), and mobilized assistance from the WHO GIS centre to support the project implementation. Bujumbura Marie Sud and Kabezi health districts, both part of the capital city Bujumbura were chosen for the pilot because their proximity to the central level allowed for better coordination and monitoring. One of the districts is primarily urban and the other rural, allowing for experience to be gained for both contexts.

The second step involved conducting a rapid assessment to evaluate the availability and quality of spatial data for the targeted areas. This process included developing a list of data sets required to produce base maps, identifying data gaps and additional data sources as well as collecting both publicly available data sets (including satellite imagery) and datasets from local sources. The available datasets included hand drawn maps and Excel files from the recently concluded paper-based microplanning workshops in the two districts.

The rapid assessment allowed the team to discard obsolete, erroneous data, inaccessible Internet links or data that were not relevant to the objectives of the digital microplanning and resulted in the development of the base maps for the selected areas.

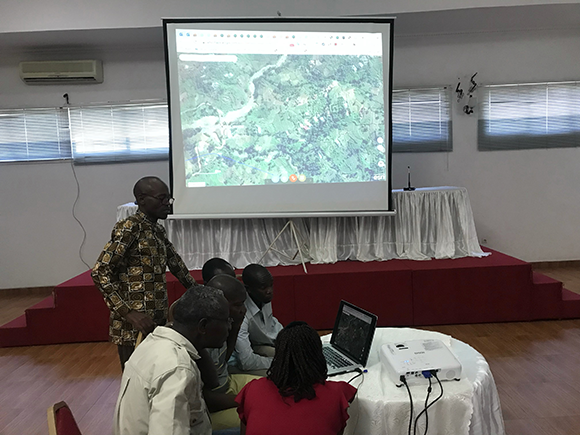

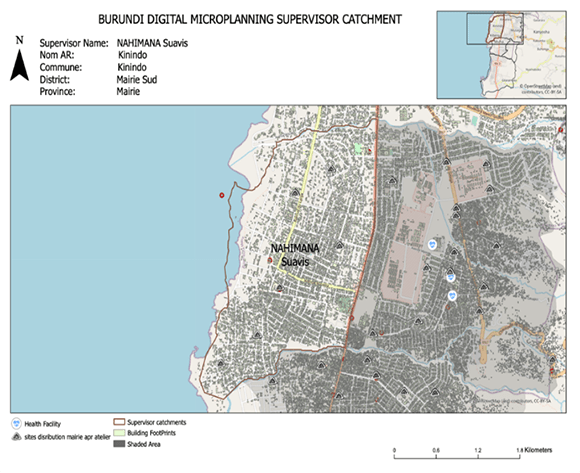

The third step was to define the objectives of the workshop and ensure that the right people would be present for the geo-spatial mapping. The workshop objectives were two-fold: (a) train the teams on the digitalization process, to create an understanding of the digital maps and generate confidence in their accuracy and value, and (b) compare the digital maps with the existing hand drawn paper maps and improve and refine the latter for greater accuracy and relevance (see both the digital and hand drawn maps below of a catchment area of Kinindo Health Centre).

What were the results and lessons learned?

Hand drawn map of Kinindo Health Centre catchment area.

Key outcomes of the workshop in Bujumbura Mairie Sud district included the demarcation of the catchment areas and upward revision of the campaign target population, which in turn led to the update of the microplans including an increase in the number of distribution points from 34 to 44. Due to time constraints, the geo-spatial mapping and comparison with paper-based microplans were not fully completed in Kabezi district.

Major takeaways from the digital microplanning pilot included:

- Identifying landscape patterns and administrative borders using digital maps is more challenging in rural settings

- The need to set an acceptable travel distance for households to reach a distribution point should take into consideration whether it is a rural or urban setting

- The importance of access to stable and reliable Internet connection for using an online platform

- The need for local high-resolution printing capability for the geo-spatial maps to facilitate their update by workshop participants

The more accurate digital map of Kinindo Health Centre catchment area allows for better planning of household registration and ITN distribution.

Use of geospatial maps for microplanning does not require all the workshop participants to be experts or have background skills in GIS. Experts at national level can lead the exercise, with focal persons in each district that have learned enough of the tools to facilitate the workshops. For most participants, they only need to work with the facilitation team to define their areas and the distribution points.

This pilot exercise clearly demonstrated the improved accuracy of digital maps versus hand drawn maps for the microplanning process. It also identified key lessons learned for the planning of future digitalized microplanning workshops if that is the direction that the NMP takes. While the development of hand drawn maps has tended to be a highlight of the microplanning process in the past, and while digitalization has its own set of challenges, relying on more accurate maps helps to ensure that national malaria programmes can better identify populations and plan for more accurate, efficient and effective ITN distributions, ensuring that they reach all households in the areas targeted.